White Paper

Use

Cases for Social Impact Bonds

in

Schenectady, New York

by Isaac Michaels[1]

Release Date: January 10, 2014

I.

Summary

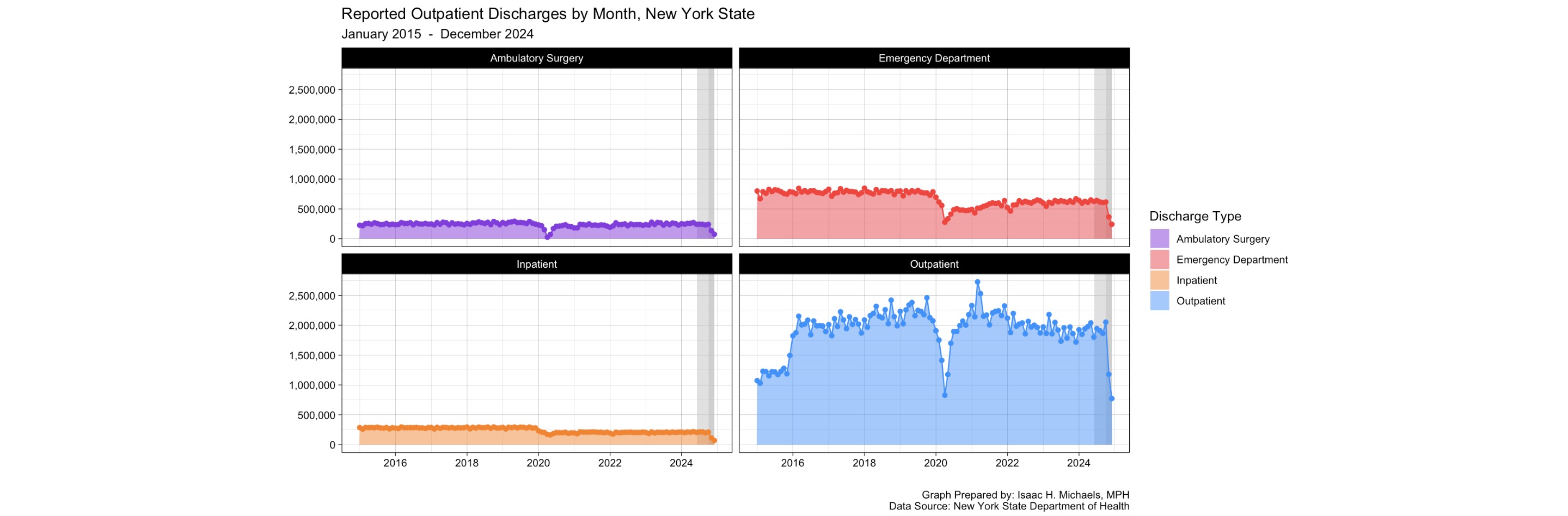

Social

impact bonds (SIBs) are financial instruments that align incentives in order to

finance socially beneficial preventive interventions using capital from

profit-seeking private investors. In particular, SIBs introduce exciting

opportunities for scaling programs to improve public health. This white paper

discusses how SIBs work, and why they are well suited for public health

applications; it is written in response to a large community health assessment

in Schenectady, New York. The paper proposes four use-cases for SIBs to be

piloted in Schenectady that would reduce incidence of asthma, falls among seniors,

type 2 diabetes, and tobacco smoking. The paper concludes with a discussion

about the future development of SIBs as a new asset class, and recommendations

for Schenectady.

II.

Introduction

Social

impact bonds (SIBs) are an emerging financial instrument for impact investing.

SIBs raise capital from profit-seeking private investors in order to fund

public interventions; appropriate interventions will produce both social impact

and government savings; the performance of the intervention is measured by an independent

evaluator; and, if the intervention achieves predetermined performance

benchmarks, then governments use the resulting savings to repay investors. By

this model, SIBs create opportunities for investors to profit; and, governments

only pay for outcomes successfully achieved.

The

first SIB ever developed was launched in the United Kingdom in 2010. Since

then, others have been piloted. Today, SIBs are being used: to reduce

adolescent recidivism in New York City[2]; to reduce chronic homelessness and to support

youth aging out of the juvenile justice system in Massachusetts[3]; to fund early childhood education in Utah[4]; and to improve asthma morbidity in Fresno,

California[5]. New SIBs are being developed and implemented

throughout the United States, and in other countries.

This

white paper describes SIBs, and how they could potentially be used to improve

public health in Schenectady, New York. In particular, this paper discusses use

cases for SIBs that would scale evidence-based interventions addressing asthma,

falls among seniors, type 2 diabetes, and tobacco smoking. Beyond these

examples, there are many exciting potential applications for SIBs in public

health. I estimate that up to approximately $50 million in averted medical expenditures

and lost productivity could be saved annually by using SIBs in Schenectady to

implement the evidence-based interventions that I will outline.

III.

The Structure of a Social Impact Bond

A

SIB is not actually a bond. A bond is a financial debt instrument in which

investors loan money to a bond issuer, and then the issuer repays investor

principal at a defined interest rate over a set repayment schedule. In

contrast, a SIB is not a debt instrument; it involves a group of contractual

partnerships that finance a socially beneficial project using the resulting

future savings.

The

partnerships that comprise a SIB involve six groups:

1. A

Government

2. An

Intermediary

3. Investors

4. Service

Providers

5. Constituents

6. An

Independent Evaluator

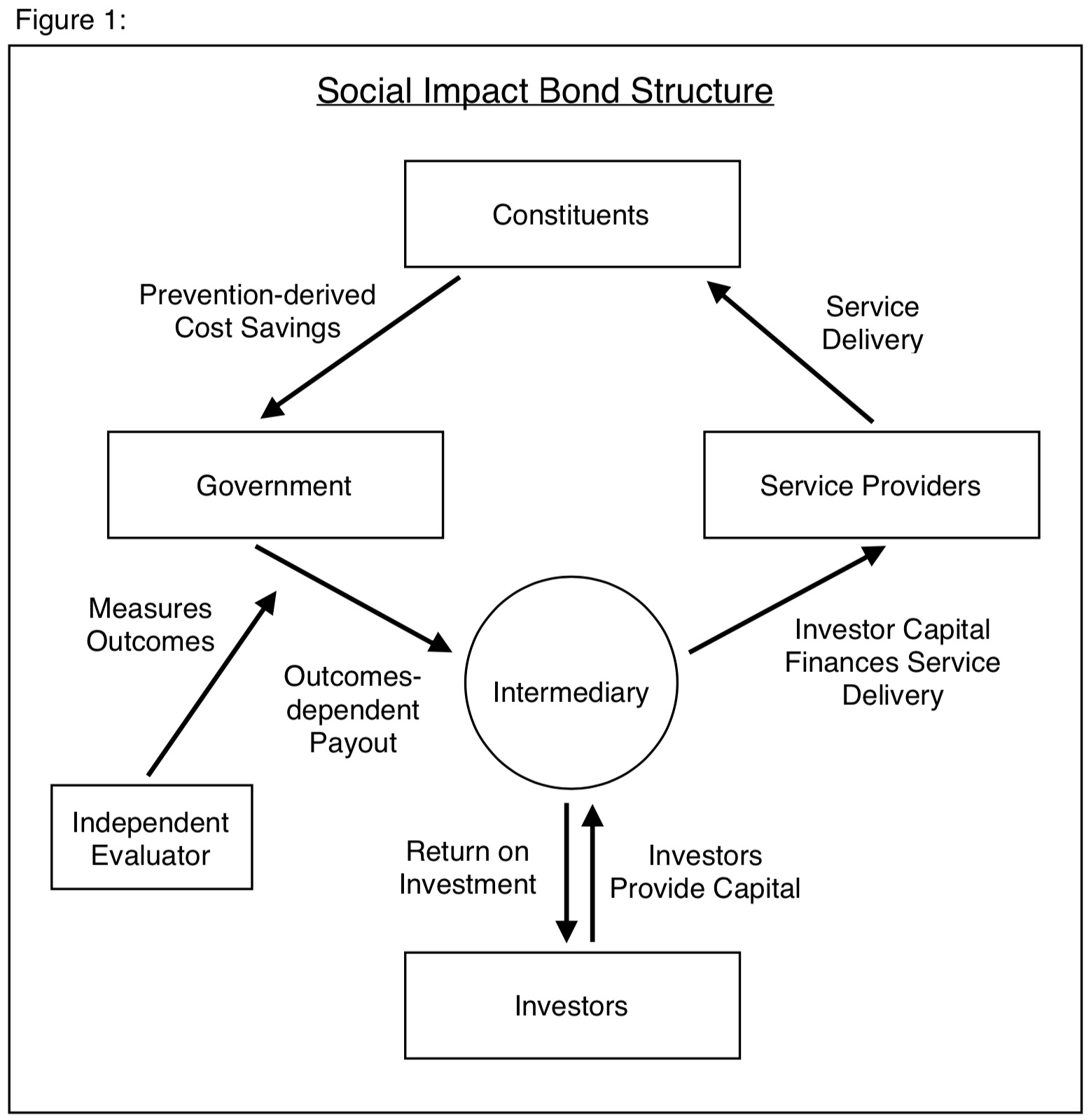

Figure

1 graphically summarizes the interactions between the six groups in a SIB.

The government initiates the formation of a SIB by contracting with an intermediary. The intermediary is tasked with raising capital from investors, and then using the capital to select, finance, and manage one or more service providers. Moreover, the intermediary is the central point of contact between the government, investors, and service providers. The selected service providers use the capital to deliver an evidence-based intervention that creates a positive social impact for constituents; appropriate interventions should generate government savings by using prevention as a means of reducing the size of publicly financed remedial programs. A best practice is to require that participating service providers be invested in the SIB in order to align incentives.

Prior

to raising investor capital, the intermediary works with the government to

define outcomes-based performance benchmarks as objectives for the

evidence-based intervention. Over the lifetime of the SIB, an independent

evaluator periodically measures the performance of the intervention based on

predetermined metrics. The gold standard for measuring the impact of an

intervention is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). RCTs are especially

well-suited for SIBs because they measure the ‘attributable impact’ created by

an intervention as well as the ’total impact’ – which could be the cumulative result of the

intervention and numerous other factors. When a RCT cannot feasibly be

performed, other measurements may be acceptable instead. SIBs can be structured

so that investors receive partial payouts when objectives are only partially

achieved; the success of the intervention at meeting performance benchmarks as

assessed by the independent evaluator would determine the amount of money that

the government gives to the intermediary to pay out to investors. SIBs with

higher rates of return for investors will be able to raise capital more easily;

however, the payout to investors should not exceed the government savings

created by the SIB. A successful SIB should achieve performance benchmarks and

desired outcomes, create government savings, return investor principal, and pay

out to investors a return on capital for taking on risk.

The

emphasis on outcomes is essential. By measuring impact on the basis of outcomes

rather than on units processed, SIBs remove the incentive for service providers

to ‘cherry pick’ the easiest available cases[6]. For example, investors in a SIB designed to

reduce youth recidivism through behavioral counseling should not be compensated

based on the recidivism rate among the children who were counseled; this would

incentivize service providers to only treat the children least likely to

recidivate in the first place. A more appropriate evaluation metric would be

the community-wide rate of youth recidivism; this metric incentivizes service

providers to target the children most likely to recidivate for counseling, and

has the government pay only for successfully achieved community-wide outcomes.

Importantly,

the direct cost-savings that SIBs achieve are not necessarily produced

immediately. A SIB designed to reduce youth recidivism in the juvenile justice

system, for example, will take less time to begin producing cost savings than

will a SIB designed to reduce the incidence of a cancer with a decades-long

latency period. Governments must consider this when developing a SIB, because

they need to include in their budgets capital to pay out to investors.

Governments with poor credit ratings may find when their intermediary raises

capital for a SIB, that investors demand a higher rate of return to compensate

for counterparty risk. If a government is interested in developing a SIB, but

has insufficient capital to pay out investors, then it might consider issuing a

bond. If the present value of the future savings from a SIB is greater than the

cost of paying investors, then a bond can provide governments with capital for

investor payout for SIBs that do not immediately produce government savings.

IV.

Health Impact Bonds

A

SIB that focuses on improving public health is sometimes referred to as a ‘health

impact bond’. The service provider in a health impact bond should deliver a

preventive evidence-based public health intervention that reduces morbidity and

mortality, and thereby creates government savings through averted Medicare

expenditures, Medicaid expenditures, lost productivity, and other public costs.

Health

impact bonds are unique in the sense that the direct savings they create extend

beyond averted government expenditures; by reducing morbidity, health impact

bonds create direct savings for private health insurance providers as well.

This introduces the potential for health impact bonds to be developed by health

insurance companies, either in place of governments, or collaboratively in

partnership with governments. In situations where a public health intervention

could create direct savings for both a government and a private health

insurance provider, the two parties could partner in forming a health impact

bond in which they would divide the responsibility of returning capital to

investors proportionately based on the relative share of the resulting savings

they will experience. For example, consider hypothetically an evidence-based

public health intervention designed to reduce hospitalizations and emergency

department (ED) utilization in a

community by improving access to preventive healthcare; if direct savings

estimates were to suggest that 70% of the savings would benefit the state

government through averted Medicaid expenditures, and 30% of the savings would

benefit a regional health insurance company, then the state government and the

health insurance company could partner in developing a health impact bond by

agreeing to provide 70% and 30%, respectively, of the capital returned to

investors. In certain cases, partnership in a health impact bond could appeal

to both governments and insurance companies; governments would be able to share

the burden of compensating investors; and the cost of capital to be paid out to

investors would be lower for a public-private partnership than it would be for

an insurance company acting independently.

V.

Social Impact Bond Value Proposition

By

aligning incentives, SIBs create opportunities for mutual benefit:

Governments

SIBs

save governments money by replacing remedial programs with preventive intervention.

By engaging private capital, SIBs can mobilize interventions that otherwise

would be unaffordable for governments to finance themselves. Furthermore, by

transferring risk to investors, SIBs enable governments to pay only for

outcomes successfully achieved.

Investors

SIBs

are the growing focus of interest among investors seeking a ‘double bottom-line’

of financial return and positive social impact. Moreover, SIBs represent a new

asset class; it is unlikely that their performance will be correlated with

other investments, and so SIBs may be an appealing solution for certain

investors seeking diversification.

SIBs

may become especially attractive investments for banks. In the United States,

certain SIBs may qualify for CRA credit under the Community Reinvestment Act[7]. This creates opportunities for banks to comply

with the mandates of the Community Reinvestment Act, and yield a financial

return on investment. Investment banks are already responding. Goldman Sachs’ Urban

Investment Group has invested in SIBs in the United States, and intends to

pursue CRA credit[8]; their Urban Investment Group’s GS Social Impact Fund has a target size of $250 million

[9]. In November of 2013, Morgan Stanley announced

the launch of the firm’s Institute for Sustainable Investing[10]; Morgan Stanley has set a five-year goal of

investing $10 billion in impact investments[11].

Constituents

Constituents

benefit directly from SIB interventions. The type and magnitude of benefits

derived are specific to the intervention and target population, and usually

involve both direct and indirect benefits. SIBs can be drivers of job creation

and economic growth in communities; they employ service providers,

intermediaries, and independent evaluators, they can be designed to stimulate

urban renewal, and certain SIBs can direct investment into sustainable

industries and job training programs. Most importantly, SIBs allow innovative

evidence-based interventions to be implemented that could be too novel for

governments to finance themselves with taxpayer funds[12].

VI.

Public Health in Schenectady, New York

Schenectady

is a small city of 66,000 residents in upstate New York, where it is part of

New York’s Capital District[13]. In Schenectady County, the urban city of

Schenectady is surrounded by suburban and rural towns. In 2013, local

organizations were brought together to form the Schenectady Coalition for a

Healthy Community; the coalition was tasked with conducting a community health

assessment, and developing a health-focused community action plan. The

Coalition proceeded by commissioning the UMatter

Schenectady Survey.

The

UMatter survey was a city-wide, neighborhood-level

health assessment administered door-to-door by teams of community health

workers equipped with iPads. The iPads contained up to 283 questions covering a

variety of personal and community health topics. A response-dependent skip

logic programmed into the survey software determined the number of questions

asked of each participant.

Between

February and May of 2013, the UMatter survey

collected 2,074 responses from city residents. Schenectady’s two highest-needs

neighborhoods were intentionally oversampled. The survey’s methods and results

are reported in greater detail in the Coalition’s 2013 Health Needs Assessment

and Community Action Plan, available online[14].

Epidemiologists

analyzed the survey results and reported back to the coalition. Based on the

epidemiologists’ recommendations and analysis, presentations from local

healthcare providers, a voting system, and well defined prioritization

criteria, the coalition members ranked the city’s prevailing public health

issues that most urgently needed to be addressed. The coalition ranked the

following public health issues as the five leading priorities:

1. Mental Health/Substance Abuse

2. Inappropriate Emergency

Department Utilization

3. Teen Pregnancy

4. Diabetes and Obesity

5. Smoking and Asthma (and

Neighborhood Safety)

I

used the findings from the UMatter Schenectady Survey

to assess the suitability for public health-focused SIBs to be implemented in

Schenectady. The following four sections of this white paper outline promising

use cases. Three of the use cases (asthma, type 2 diabetes, and tobacco

smoking) address public health issues that the coalition included in their top

five priorities. One of the use cases (falls among seniors) addresses a public

health issue that the coalition identified as an urgent priority, but did not

include as one of the top five.

VII.

SIB Case: Asthma

Asthma

is especially prevalent among children in urban environments. Below are key

incidence metrics for Schenectady County:

• Asthma ED visits in Schenectady County from 2005-2007 = 3,080 [15]

• Asthma hospitalizations in Schenectady County from 2005-2007 = 637 [16]

From

2005 to 2007, there were an average of 1,026 and 212 asthma-related ED visits

and hospitalizations, respectively, in Schenectady County. The US Census

estimates that in 2012 the city of Schenectady and Schenectady County had

populations of 66,078 [17], and 155,124 [18] respectively. Asthma is often disproportionately prevalent in urban

environments; this suggests that the asthma incidence rate is higher in the

city of Schenectady than in Schenectady county. However, if we assume that

these incidence metrics and demographics are relatively stable, and that the

asthma incidence rate in the city of Schenectady is similar to that of the

county, then we can assume that asthma annually causes approximately 437 ED

visits and 90 hospitalizations in the city.

In

2007, the average cost of an asthma ED visit was $151, and the average cost of

an asthma hospitalization was $6941 [19]. By applying these average costs to our ED visit

and hospitalization estimates, we can estimate that asthma-related

hospitalizations and ED visits in the city of Schenectady annually cost

approximately $690,677.

The

National Cooperative Inner City Asthma Study found that a multi-faceted in-home

tailored intervention was effective at controlling asthma symptoms and reducing

morbidity[20]. This preventive intervention involved home

environmental assessments, education, and, the use of mattress covers, pillow

covers, HEPA vacuums, HEPA air filters, smoking cessation, pest management,

minor repairs, and intensive household cleaning. The study found that, in

children, the intervention lead to a median decrease of 21 asthma symptom days

per year, a median decrease of 12 missed school days per year, and a combined

median decrease of 0.57 acute healthcare visits per year. In adults, the study

found only borderline or no improvement in healthcare utilization.

In

children, the intervention was successful at cost-effectively producing cost

savings through minor or moderate environmental remediation with an educational

component. The cost savings came in the form of averted asthma care

expenditures and improved productivity. For participants who required minor or

moderate environmental remediation, the cost of the program per participant was

between $231 and $3,796; the program cost per participant was $3,796 to $14,858

when major environmental remediation was necessary. Ultimately, cost-benefit

studies determined that the intervention generates $5.30 to $14.00 in return

for every dollar invested.

The

cost-benefit analysis suggests that a SIB would be a sustainable vehicle for

scaling up asthma prevention in the city of Schenectady. Additional study is

still needed beyond these preliminary estimates in order to better understand

asthma-related costs, as well as to better assess the suitability of the multi-faceted

intervention for Schenectady. City-wide asthma-related hospitalization/ED

visits could be good outcome metrics for an asthma-focused SIB.

VIII.

SIB Case: Falls Among Seniors

Schenectady

County experiences a high incidence of falls among seniors, as well as a

fall-related mortality rate that exceeds the New York State average. Below are

three important measures of incidence:

• Mean Annual Frequency of Emergency Department Visits due to Falls in

Residents Ages 65+, 2006-2008 in

Schenectady County = 1,101 [21]

• Mean Annual Frequency of Hospitalizations due to Falls in Residents

Ages 65+, 2006-2008 in Schenectady County = 543 [22]

• Mean Annual Frequency of Mortality due to Falls in Residents Ages

65+,

2006-2008 in Schenectady County = 9 [23]

The

US Census estimates that in 2012, Schenectady County’s ages 65 and older

population was 23,423 [24]. The Census also estimates that in 2012, the city of Schenectady had

a population of 66,078, and that in 2010 11.4% of the city’s population (7,532)

was age 65 or older[25]. Altogether, if we assume that these rates and demographics have

remained relatively stable and that incidence rates in the city are similar to

those in the county, then we can assume that 32% of of

seniors in Schenectady County reside within the city of Schenectady, and we can

estimate that the city annually experiences approximately 354 ED visits, 174

hospitalizations, and nearly 3 deaths due to falls among seniors.

The

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the

average Medicare costs per fall are between $9,113 and $13,507 [26]. The average costs of a fall-related ED visit is

probably different than the average cost of a fall-related hospitalization.

However, if we apply the CDC’s average Medicare costs to our ED and

hospitalization estimates, then we can estimate that fall-related ED visits and

hospitalizations in seniors ages 65 and older in the city of Schenectady cost

between $4,811,664 and $7,131,696 annually.

The

Falls-HIT (Home Intervention Team) Program is a fall prevention intervention

that involves home visits by occupational therapists and supports home

modification to improve safety[27]. A study found that the Falls-HIT Program reduced

the fall rate among participants by 31% [28]. Based on the previous cost estimates, if the

Falls-HIT Program were implemented with similar efficacy throughout

Schenectady, then it could produce between $1,491,615 and $2,210,825 in annual

savings through fall prevention.

These

preliminary estimates suggest that fall prevention could be a viable use case

for SIBs. Moving forward, more investigation would be necessary to better

understand fall prevalence within the city, associated costs, as well as the

scalability and efficacy of a fall prevention program in Schenectady. Fall

prevention produces direct savings through averted healthcare costs, and so a

fall prevention SIB could be well suited for facilitating a partnership between

public and private health insurance providers. Appropriate outcome metrics for

this type of SIB would be hospitalization, ED visits, and mortality due to

falls per 10,000 population age 65 and older in the city of Schenectady.

IX.

SIB Case: Type 2 Diabetes

Type

2 diabetes is epidemic in New York State[29]. Results from the UMatter

Schenectady Survey indicate that the prevalence in the city is high:

• 11.6% of all UMatter

respondents reported that they had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes by a

health professional[30].

• Among non-diabetic UMatter

respondents, 13.9% reported that they had been diagnosed with pre-diabetes by a

health professional[31].

Type

2 diabetes is an expensive chronic disease to manage. The average annual cost

of healthcare for a person with diabetes is $11,744, of which $6,649 is

attributable to diabetes[32]. In contrast, the average annual cost of healthcare for a

non-diabetic is $2,560 [33]. All respondents in the UMatter survey

were ages 18 and older; the US Census estimates that in 2012, the city’s 18 and

older population was 49,954 [34]. From the UMatter

findings, we can estimate that in the city’s 18 and older population, there are

approximately 5,794 people with type 2 diabetes, and 6,138 people with

pre-diabetes. By this, we can further estimate that among adults in the city of

Schenectady, annual medical expenditures attributable to type 2 diabetes amount

to approximately $38,524,306.

The

National Diabetes Prevention Program is an evidence based intervention that reduces

the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58% in people with pre-diabetes[35]. The program is available in Schenectady[36], but the capacity is restricted by maximum class

sizes and the availability of personnel and facilities. A SIB could be effective

at scaling the program. If the National Diabetes Prevention Program were

expanded in Schenectady, it could prevent up to 3,560 people with pre-diabetes

from developing type 2 diabetes, and would thereby generate up to $26,775,124

in annual savings through averted healthcare expenditures attributable to

diabetes.

The

cost of diabetes and efficacy of preventive intervention together suggest that

a diabetes-focused SIB could be effective in Schenectady. More investigation

should be conducted to measure pre-diabetes prevalence, and to more precisely

estimate the scalability and efficacy of the National Diabetes Prevention

program in Schenectady. An appropriate outcome metric for this SIB could be

type 2 diabetes incidence in the city of Schenectady.

X.

SIB Case: Tobacco Smoking

According

to the CDC, tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in the United

States, and life expectancy is 10 years shorter for people who smoke[37]. The UMatter survey

found that 37.1% of respondents are current smokers; all respondents in the

survey were ages 18 and older[38]. In 2012, the city of Schenectady had 18 and

older population of 49,954 [39]. Altogether, we can estimate that there are

approximately 18,532 adult smokers in Schenectady.

Based

on data from a 2008 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the American

Lung Association estimated that smoking cost an average of $4,260 per adult

smoker in lost productivity and direct healthcare expenditures in 2004 [40]. If we assume that the cost of smoking has

remained relatively constant since 2004, then the American Lung Associations

estimation suggests that the cost of adult smoking in Schenectady is

approximately $78,946,320 annually.

The

UMatter Schenectady Survey found that although

smoking prevalence in Schenectady is high, there is also great interest in

cessation. The survey found that 49.2% of current smokers have tried to quit

within the last year; out of these respondents, 65.2% reported that they

attempted to quit without assistance by going ‘cold turkey’[41]. For many smokers, assisted quit programs can be

more effective. In a 2000 study, Zhu et al. found that smokers who tried

to quit with assistance (15.2%) were more successful than those who tried to

quit unassisted (7.0%) [42].

The

Butt Stops Here is a one-on-one counseling program that, cooperatively, is

hosted in Schenectady at Ellis Hospital and run by Seton Health of the

Albany-based St. Peter’s Health Partners. The program achieves a 30% quit rate[43]. With greater access to capital and a scaled up

referral system, The Butt Stops Here could increase its service capacity. A SIB

could be an effective solution. Up to $11,653,289 could be saved annually by

extending The Butt Stops Here to adult smokers in Schenectady who have tried to

quit in the last year; up to $23,685,548 in annual savings could be achieved by

extending the program to all of Schenectady’s adult smokers.

A

SIB for smoking cessation and prevention in Schenectady could produce

significant cost savings by scaling new or existing programs. Smoking

prevalence, as measured by the UMatter Schenectady

Survey or other public health surveillance systems, would be an appropriate

outcome metric for evaluating the success of the intervention.

XI.

Discussion and Recommendations

The

evidence-based interventions outlined in the preceding sections can improve

Schenectady’s public health and generate savings:

SIB Use Case Estimated Total Savings

• Asthma prevention $5.30

to $14.00 per dollar invested

SIB Use Case Estimated Annual Savings

• Fall prevention among seniors Between

$1,491,615 and $2,210,825

• Type 2 diabetes prevention Approximately

$26,775,124

• Tobacco Smoking cessation Approximately

$23,685,548

I

recommend that Schenectady explore these, and other opportunities for

developing public health-focused SIBs. I also recommend that the city work

collaboratively to develop SIBs in partnership with New York State and with

private health insurance companies.

Importantly,

the SIB use cases in this report only present preliminary estimates of maximum

possible cost savings. The estimates do not account for costs of developing and

deploying SIBs, such as contracting with intermediaries and compensating

investors. Further analysis should be conducted for each use case in order to

better estimate prevalence, incidence, and costs attributable to morbidity and

mortality. In addition, the interventions to be considered should be

evidence-based, ethical, and they should be chosen on the basis of feasibility,

scalability, and probable efficacy in Schenectady.

Schenectady

is well suited for developing and deploying a health impact bond. It is the

only city in upstate New York’s geographically second smallest county; it is

served by a county health department, a single acute care hospital with a

formal outpatient campus, and a Medicaid Health Home; and Schenectady is

located in a region with significant academic resources. Schenectady can draw

on services and expertise from an organized community-wide coalition of health

and community service providers; and, the majority of non-government health

insurance in Schenectady is provided by two regional not-for-profit health

plans.

SIBs

are a relatively new invention, and the regulatory framework that governs them

is still developing at the state and federal levels. The two SIB pilots now

underway in New York City and New York State demonstrate that SIBs can legally

be developed in New York’s largest city, and within a designated state program.

Schenectady is generally subject to the more restrictive provisions of the

state’s Local Finance Law, and therefore should consult with legal experts and

perhaps consider requesting special state legislation.

As

the adoption of health impact bonds continues, I hope that accountable care

organizations, patient-centered medical homes, and employers will join

governments and health insurance providers as partners in health impact bond

development. In the future, health impact bonds could become major drivers of

investment into public health. Furthermore, they could create economic

incentives for deploying resources for addressing neglected public health

challenges that before were unprofitable.

I expect that SIBs will grow tremendously as an asset class. I predict that in the future, SIBs will be able to raise investor capital through formal initial public offerings, and I expect that SIB shares will be traded on dedicated exchanges as dividend-yielding securities. This could perhaps give rise to the creation of ‘exchange-traded SIB funds’ (ETSFs) that would enable investors to make diversified or sector-specific impact investments across multiple SIBs. In the future, it would be interesting to see the first ever ‘immunization ETSF’, ‘clean water ETSF’, ’cancer prevention ETSF’, ’pollution reduction ETSF’, or ’New York State ETSF’.

[1] MPH Candidate, Epidemiology; University at Albany, School of Public

Health.

Email: imichaels@albany.edu.

[2] Bloomberg, M. R. (2012, August 02). Bringing social impact bonds to New York City. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/om/pdf/2012/sib_media_presentation_080212.pdf

[3] Massachusetts Executive Office of Administration and Finance, (2012). Massachusetts first state in the nation to announce initial successful bidders for ‘pay for success’ contracts. Retrieved from website: http://www.mass.gov/anf/press-releases/fy2013/massachusetts-first-state-in-the-nation-to-announce-ini.html

[4] Fact sheet: the Utah High Quality Preschool Program America’s first social impact bond targeting early childhood education. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.goldmansachs.com/what-we-do/investing-and-lending/urban-investments/case-studies/impact-bond-slc-multimedia/fact-sheet-pdf.pdf

[5] Badawy, M. (2012, October 19). California city seeks to cut asthma rate via bond issue. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/10/19/us-investing-impactbonds-health-idUSBRE89I0U120121019

[6] Disley, E., Rubin, J., Scraggs, E., Burrowes, N., & Culley, D. U.K. Ministry of Justice, (2011). Lessons learned from the planning and early implementation of the social impact bond at HMP Peterborough. Retrieved from website: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/217375/social-impact-bond-hmp-peterborough.pdf

[7] Goldberg, S. H. (2013, January). Do sibs qualify for the Community Reinvestment Act? oh, yeah. SIB TRIB, (2), 14. Retrieved from http://payforsuccess.org/sites/default/files/sib_trib_no._2.pdf

[8] ibid.

[9] GS social impact fund. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/focus-on/impact-investing/touts/fact-sheet.pdf

[10] Morgan Stanley establishes institute for sustainable investing. (2013, November 1). Retrieved from http://www.morganstanley.com/about/press/articles/a2ea84d4-931a-4ae3-8dbd-c42f3a50cce0.html

[11] Institute for Sustainable Investing. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.morganstanley.com/sustainableinvesting/

[12] Eddy, M. (2012, September). Scaling tuberculosis treatment through a social impact bond. Instiglio, 5. Retrieved from http://www.instiglio.org/pub/Instiglio%20White%20Paper%20-%20Tuberculosis%20Social%20Impact%20Bond.pdf

[13] U.S. Census Bureau. (2013, December 13). State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady County, N.Y. Retrieved January 25, 2007, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/36/3665508.html

[14] Pratt, D., & Buckenmeyer, E. (2013, November 15). 2013 community health needs assessment and community action plan: a consolidated, multi-agency, community-wide plan for action to improve the health of people in Schenectady, New York. Schenectady Coalition for a Healthy Community, Retrieved from http://www.schenectadychamber.org/files/814.pdf

[15] New York State Department of Health, Center for Community Health. (2009). New York State asthma surveillance summary report. Retrieved from website: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/ny_asthma/pdf/2009_asthma_surveillance_summary_report.pdf

[16] ibid.

[17] U.S. Census Bureau. (2013, December 13). State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady (city), N.Y. Retrieved January 25, 2007, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/36/3665508.html

[18] U.S. Census Bureau, State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady County, N.Y.

[19] New York State Department of Health, Center for Community Health, Asthma surveillance summary report.

[20] Jacobs, D. E., & Baeder, A. (2009). Housing interventions and health: a review of the evidence. National Center for Healthy Housing, Retrieved from http://www.nchh.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=2lvaEDNBIdU=&tabid=229

[21] New York State Department of Health, Injury Prevention Program. (2010). Incidence of unintentional fall injuries, ages 65+ emergency department (ed) visits new york state residents, 2006-2008. Retrieved from website: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/prevention/injury_prevention/docs/2006_2008_falls_ed65 county.pdf

[22] New York State Department of Health, Injury Prevention Program. (2010). Incidence of unintentional fall injuries, ages 65 hospitalizations new york state residents, 2006-2008. Retrieved from website: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/prevention/injury_prevention/docs/2006_2008_falls_hospital65 county.pdf

[23] New York State Department of Health, Injury Prevention Program. (2010). Incidence of unintentional fall injuries, ages 65 deaths new york state residents, 2006-2008. Retrieved from website: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/prevention/injury_prevention/docs/2006_2008_falls_deaths65 counties.pdf

[24] U.S. Census Bureau, State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady (county), N.Y.

[25] U.S. Census Bureau, State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady (city), N.Y.

[26] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. (2013). Cost of falls among older adults. Retrieved from website: http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/fallcost.html

[27] Stevens, J. A. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. (2010). A CDC compendium of effective fall interventions: what works for community-dwelling older adults, 2nd edition. Retrieved from website: http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/pdf/cdc_falls_compendium_lowres.pdf

[28] ibid.

[29] New York State Department of Health, Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention. (2011). Dual epidemics of diabetes and obesity are on the rise among New York State adults. Retrieved from website: http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/prevention/injury_prevention/information_for_action/docs/2011-4_ifa_report.pdf

[30] Pratt, D., & Buckenmeyer, E., “2013 community health needs assessment and community action plan”.

[31] ibid.

[32] Dall, T., Edge Mann, S., Zhang, Y., Martin, J., Chen, Y., & Hogan, P. (2008). Economic cost of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care, 31(3), doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017

[33] New York State Department of Health, (2012). Diabetes. Retrieved from website: http://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/conditions/diabetes/

[34] U.S. Census Bureau, State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady (city), N.Y.

[35] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2013). National Diabetes Prevention Program. Retrieved from website: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/about.htm

[36] YMCA diabetes prevention program. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.cdymca.org/healthyliving/diabetes.aspx

[37] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2013). Tobacco-related mortality. Retrieved from website: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/tobacco_related_mortality/index.htm

[38] Pratt, D., & Buckenmeyer, E., “2013 community health needs assessment and community action plan”.

[39] U.S. Census Bureau, State & county Quickfacts: Schenectady (city), N.Y.

[40] American Lung Association, (n.d.). Smoking. Retrieved from website: http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/about-smoking/health-effects/smoking.html

[41] Pratt, D., & Buckenmeyer, E., “2013 community health needs assessment and community action plan”.

[42] Zhu, S., Melcer, T., Sun, J., Rosbrook, B., & Pierce, J. (2000). Smoking cessation with and without assistance: a population-based analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 18(4), 305-11. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10788733

[43] ‘The Butt Stops Here’ smoking cessation Troy support group. (2010, June 28). Retrieved from http://www.setonhealth.org/news_events/event_detail.cfm?ID=286